Tomaso Albinoni: From Baroque Obscurity to Rock Immortality

- David Lapadat | Music PhD

- Aug 1, 2025

- 11 min read

*This text is based on a presentation I held within the conferences sessions at Key Festival, at the University of Music Bucharest, in 2021, celebrating 350 years from the birth of Albinoni.

The Birth and Legacy of a Baroque Composer

Tomaso Giovanni Albinoni was born in 1671 into a wealthy family in “La Serenissima,” as Venice was known.

Albinoni became a prolific Baroque composer and left behind an impressive number of musical works upon his death in 1751, with manuscripts ending up in the State Library in Dresden.

Known in his time mainly for his operas, as years passed and Baroque gave way to Classicism, which subtly turned into Romanticism, and finally when the Romantic Era could no longer withstand the 20th century with the same vigor it dominated the 19th, losing itself among numerous modern directions through which music tried to express itself, Albinoni’s name survived in Italy on the edge of anonymity among famous Italian Baroque names starting with Monteverdi, continuing with Vivaldi, and ending with Pergolesi.

Albinoni’s music almost got lost in Europe in the mighty shadow of German Baroque (Bach, Händel, or Telemann), French Baroque (Lully, Couperin, and Rameau), or British (Henry Purcell and again Händel).

The Loss and Recovery of Manuscripts

In 1945, following Allied bombings, the Dresden library was destroyed, and a large part of the manuscripts were lost forever.

That same year, Italian musicologist Remo Giazotto began rewriting Albinoni’s life, managing to recover some manuscripts from Dresden.

In 1958, Giazotto reorchestrated from fragments the Adagio in G minor, an unknown work by Albinoni, dating it to 1708.

Giazotto claimed that, starting from Albinoni’s ideas (basso continuo and a few melodic fragments), he could reconstruct the entire piece following Baroque compositional rules. Thus, the composition credits could appear as: composer – Tomaso Albinoni, orchestrator/arranger – Remo Giazotto.

The supposed fragments from which the Italian musicologist started the reconstruction were never discovered.

For this reason, over time, musicologists and critics have labeled Giazotto’s story as fiction, and the Adagio as exclusively Remo Giazotto’s work. Thus, one of the most famous Baroque pieces was written 200 years after the end of the Baroque Period.

Beyond Disputes: Lasting Fame

Beyond musicological disputes about the work’s paternity, one thing is certain: Tomaso Albinoni’s name gained unexpected notoriety through the Adagio in G minor, the piece being used throughout the 20th century in films, commercials, and even today enjoying millions of views on YouTube under the name Albinoni – Adagio in G Minor.

The piece continues to be presented in concerts, discographies, on YouTube, as Albinoni’s work.

Starting in 1958, Tomaso Albinoni began to be known not only throughout Europe, his fame crossing the Atlantic and reaching the American continent.

There, in the United States, where the star typology was born, where the celebrity status was invented, existed the environment to support and propagate fame.

That environment was called pop culture.

In this whirlwind encompassing works of art, films, poets, writers, musicians, rock bands, dissidents, rebels and revolutionaries, vagabonds and aristocrats, cultured people and common folk, in this whirlwind, therefore, the Adagio in G minor was caught, along with the myth of its origin, and with it, Tomaso Albinoni.

A Coincidental Connection: Albinoni Meets Morrison

Coincidence has it that in 1971, less than a month after the 300th anniversary of Albinoni’s birth, on July 3, in Paris—the dream city for American writers self-exiled in the interwar period—Jim Morrison, the lead singer of The Doors, died far from home.

Leaving behind the spotlight to seek the peace of mind any writer needs, Morrison traded his musician life to become a poet.

Seeking peace, he slipped toward death, and the first step toward poetry meant the first step toward legend.

A substantial legacy, materialized in songs and poems, was Morrison’s gift to art lovers. At the same time, The Doors members Ray Manzarek, Robby Krieger, and John Densmore knew how to honor Jim and cherish his memory.

Before leaving for Paris, Morrison (between 1969 and 1970) recorded himself reading numerous ideas, poems, and narratives.

After his death, the three Doors decided to compose orchestrations to accompany Jim’s recited verses and make them known worldwide.

In 1978, the album An American Prayer was born.

On this album, we can follow how one of Morrison’s most penetrating poems unfolds calmly, undisturbed, against the sonic background provided by the Adagio in G minor.

Thus, perhaps unknowingly, while resting alongside Molière, Delacroix, Bizet, Chopin, Enescu, Balzac, Proust, Wilde, Gertrude Stein, or Édith Piaf at Père Lachaise cemetery, Morrison met in 1978 in the universe he had just left, with Albinoni.

The Doors’ Inspiration and Adaptation

By An American Prayer, The Doors had composed six studio albums with Jim and two post-Morrison albums.

Lack of inspiration couldn’t have been a decisive factor in adopting the Adagio in G minor to build the soundtrack for An American Prayer.

Judging by the strange soulful fit between poetry and music, we can say The Doors merely brought together two components that were searching for each other, thus obtaining a new standalone artistic fact.

Morrison’s poem The Severed Garden meets the Adagio in G minor and, transfigured by The Doors’ intuition, transforms into A Feast of Friends.

The Doors’ great asset was always the group’s ability to bring various musical styles and genres close to rock. We discovered in Break on Through (To the Other Side) a stylistic blend of bossa nova, jazz, and blues-rock.

In The End, Indian music is skillfully integrated into rock, not a superficial borrowing of raga music or sound.

In Riders on the Storm, country music appears in the psychedelic tableau where “riders on the storm” unleash.

And in the case of the Adagio in G minor, Baroque music is brought toward rock style.

A Feast of Friends reprises the first two themes from the Adagio.

Old elements are carefully taken and discerningly rearranged in the new ensemble that will sing them.

New ones, like bass guitar, electric guitar, and drums—foreign to Baroque music—are inserted discreetly and grow in intensity naturally, with the piece’s dramatic evolution.

Morrison’s Mystical Poetry

Morrison’s poems are shrouded in mystery; unknown metaphors are born as verses unfold, featuring monstrous creatures and supernatural beings.

Surreal images succeeding in a cinematic manner, archaic symbols joining modern city elements, enhance the ambiguity of Morrison’s poems and, at the same time, are so many ways through which Jim expresses his spiritual beliefs.

Morrison fears spiritual death more than physical death.

Musical Familiarity and Innovation

From the first measure of A Feast of Friends, the listener is drawn by the familiarity of the musical frame subconsciously referring to the Adagio in G minor.

Indeed, verses enter only on the third beat of the second measure, and while the audience waits to clarify that familiarity, it is pushed toward something new: Morrison’s poetic universe.

The main theme from the Adagio will be revealed a bit later.

Although they share to some extent the same sonic material, the same musical themes, and poetic charge, expressively the two pieces diverge, A Feast of Friends borrowing from the aesthetics of Riders on the Storm.

Moreover, The Doors transpose the song from a ternary meter to a binary one.

Also, the sound of the organ and string ensemble score is rearranged for a rock band distribution: two electric guitars, two electric organs, bass guitar, and drums.

Expressive Dimensions: Adagio vs. A Feast

The Adagio in G minor reveals an oppressive dimension, evoking the pain of the soul that has left the body, which, in an almost religious sense, heads toward an implacable final judgment, parting from the lost life it mourns. It is the music of silence, of mute suffering.

The heart-wrenching pain of this passage is solemn, and the organ opening the piece falls like a heavy marble slab on a tomb.

The organ symbolizes the seal, the impenetrable barrier between us and mystery, between life and death.

From the abyss of this sepulchral oppression rises something unknown from the bass’s walk.

The organ’s melodic interventions resound like clock strikes, and the soul is to escape the grip and float above the theme sung by the first violin toward the secret tolls it must pass.

A Feast of Friends, on the other hand, constitutes an expectation.

It represents preparation to face the unknown, an initiation whose final exam is approaching death.

The phrase “feast of friends” suggests a secret confraternity, accessible only to the initiated.

Curiously, the organ in The Doors’ orchestration (the only common element between the two ensembles) does not take the organ part from the Adagio.

Such an omission, which seems counterintuitive, is precisely the element that changes perspective in The Doors’ reinterpretation.

Keeping the bass walk (punctuated by drum beats on time), A Feast of Friends lightens the orchestration, shedding the organ’s long harmonies and entrusting melodic interventions to the electric guitar, obtaining a ghostly, lightning sound that tries to guess the mystery.

The clock strikes retain the idea from the Adagio but change intonation. The solemn hour resounding in the Adagio in G minor transforms into the “strange hour.”

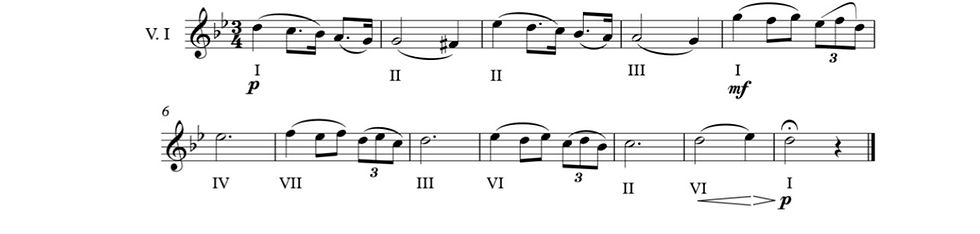

Structural Analysis: Introduction and Themes

The first part of the poem unfolds on the sonic material of the Adagio’s introductory measures, but in A Feast of Friends, the introduction is exposed twice.

On repeating the introduction, the electric organ will double the second guitar’s interventions, thus approaching the Adagio’s organ score, but The Doors’ organ part lacks the harmonic load of the Adagio, and interventions are mixed discreetly in the background.

Above the original material, taken with the small exceptions mentioned exactly as in the Baroque piece, hovers the discreet sound of the electric guitar.

With an arpeggiated walk in the first part of the introduction, the electric guitar, at the introduction’s repetition, will perform an improvisation, an original solo over the Adagio material.

These two guitar interventions represent The Doors’ original contribution and the link between musical styles.

Stylistically, the first guitar’s score and performance manner fit psychedelic rock.

Relating to the poetic text, these electric sparks, starting as consciousness’s last twitches, illuminate enough to see the hideous tableau spreading over life.

Morrison’s vision is grim.

From the first verse, he declaims: “Wow, I’m sick of doubt.”

In other words, doubt, unrest, change are life’s main traits.

The nightmare image continues. We see men like dogs, who with their evil women throw shabby blankets over “our sailors.” It is a world of crude bonds where servants share power. Mundane aspects frighten the poet.

He wants to escape the television’s gaze scrutinizing us from its high tower. Facing the danger lurking for the spirit in such a world, pushed by a Voltairian impulse, Morrison turns into Candide: “I want roses in my garden bower, dig?”.

The poet must cultivate his garden..

The blood of these lugubrious creatures, “aborted strangers,” “mutants,” must nourish the plowed soil from which plants will be born.

Thus, in the poem’s first part, we observe a permanent contrast between ugliness and beauty, truth and lie.

A dialectic between matter and spirit, apathy on one side, passivity on the other. We see ignorance’s monstrosity (men like dogs, evil women, servitude, insufferable faces, mutants, strangers) facing spiritual freedom: sailors, royal babies, rubies, and flowers.

Over all this spreads death’s veil.

The poetic thread breaks, and as a prelude to this death, the Adagio’s main theme appears, sung by the electric guitar.

The rhythm section, bass and drums, go together on the rock music pattern, here the bass line parting from the Adagio model.

Keeping the main theme, The Doors’ orchestral arrangement differs from Giazotto’s.

The electric guitar’s melodic line presents the theme fragmented, syncopated, laced with staccato interventions, an interpretation close to rock style. The electric guitar abandons first violin’s legato.

The Adagio’s dense orchestration, rich in polyphonies, reduces in A Feast of Friends to a accompanied melody.

It is important to note that such orchestration simplification was necessary and welcome in The Doors’ context.

The main element in A Feast of Friends is the recited part, Morrison’s recorded poetry.

Ghostly, evanescent, the verses subordinate the instrumental arrangement, which must project them before the orchestration.

Introduced alone at first, theme one will be accompanied by poetry starting from the second phrase’s midpoint (the theme divided into three equal phrases of four measures each).

Anticipated at the start by guitar interventions embodying clock “strikes,” the “strange hour” arrives at theme I’s midpoint, when “pale,” “disgusting,” “ghastly” death suddenly appears like a “friendly” guest invited into one’s home.

The poetry navigates on waves of pain spreading before the audience through theme one’s melodic line, built on sequence model idea.

From the orchestration’s abysses, the first organ figures harmonies through arpeggiated walk, while the second electric organ goes in parallel octaves with the melody.

Bass and drums present a simple drawing, specific to classic rock. The melodic line’s sonic material is taken varied but not far from original.

On the other hand, melody harmonization differs in The Doors. Other harmonies (degrees) are used, and chords, brought to root position, are usually simple triads.

The lyrical perspective from which death is viewed is disturbing; not due to the grotesque image, not due to the frightening feeling stirred by the strange hour’s coming, but because we see between death and soul a stirring intimacy, of which we become aware only in the last moment.

At this point, the music settles on the fermata pause, which The Doors exaggerate, leaving room for the next four verses: “Death makes angels of us all / And gives us wings / Where we had shoulders / Smooth as raven’s claws.”

Death’s image, seen as spirit’s ascension, represents the poem’s climax and, potentiated by the instrumental pause, gains heart-wrenching drama.

Death arises in all its frightening grandeur and accomplishes the soul’s ontological transfiguration.

The second theme debuts with octave parallelism executed by all instruments.

The Doors take the intention from near the Adagio’s end, when the second theme returns in another key, forte, introduced by first violin, second violin, and viola, presenting in turn parallel octaves walk in the first measure.

In the Adagio, the melodic line’s parallel walk continues at first and second violin, while in The Doors, guitars are joined by the second organ doubling the melody.

The first organ intones harmonies arpeggiated. Bass resumes its walk from the introduction, while drums beat classic rock rhythm.

The melody is harmonized differently from the Adagio here too. A Feast of Friends stays in G minor, and chords are again in root position.

Plagal relations predominate in The Doors’ version. In the first phrase, like theme one, the melody has an arched, alternating walk, stepwise or in leaps.

Less dramatic than theme one’s melody, it continues to envelop verses in an aura of unrest. Here is when the mystical world the soul entered is presented as superior to the material world: “no more money”, “no more fancy dress”.

Though appearing as the best option, “the other Kingdom” does not satisfy Morrison, who thinks death’s kingdom might involve “pale submission to a vegetable law.”

In other words, Morrison apprehensively considers that even death may submit to a natural law. He points us to William Blake’s mystical system.

Briefly, Blake considered “vegetable nature,” “vegetable body” inferior on eternity’s scale compared to imagination’s power, symbol, and visionary image.

Blake was convinced the “human soul heads triumphantly, post mortem, toward the eternal and infinite world of imagination.”

The poet declares he will not go anywhere but metaphysical imagination (“I will not go”), and starting with the second phrase (f2), the melody, built by repeating the model set in the first measure, follows its descending walk toward the final authentic cadence.

Morrison prefers the “Feast of Friends” over the “Giant Family”.

He chooses Plato’s “Symposium” over salvation, as announced in When The Music’s Over: “cancel my subscription to the Resurrection (…) / a feast of friends awaits me outside.”

The organ’s last arpeggios discreetly take the violin-sung end in the Adagio.

The melody appears as a ladder, leading to paradise in Albinoni, and in Morrison to the metaphysical abode of poets, pure understanding, and eternal contemplation.

Comments